Two days ago, Vietnam announced that the Barbie film would be banned from screenings throughout the country, citing the appearance of the nine-dash line.

The geopolitical response to this ban has been varied. A senator in the Philippines (another country with stakes in the claims to the Spratly Islands and South China Sea), Risa Hontiveros, did not call for a ban on the film, but encouraged a disclaimer to be run before the film that “that the nine-dash line is a figment of China’s imagination,” explaining that “the movie is fiction, and so is the nine-dash line.” China, on the other hand, has taken this news of the nine-dash line with “a swell of patriotic fervor.”

What is the nine-dash line and why does its inclusion in Barbie matter?

China has used the nine-dash line to lay territorial claim to land in the South China Sea (also known as the East Sea in Vietnam), including the Spratly Islands, which is jointly contested by China, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Taiwan. Over the past decade, China has been gradually increasing claims to land masses in this contested space, including adding a “wall of sand” to create artificial land masses and militarizing at least three islands.

These actions have been interpreted by many members of the international community as a sign of aggression and has escalated the tensions within East and Southeast Asia. Vietnam’s interests in the South China Sea dispute encompass both national security concerns and human security concerns. Ceding territory for China allows for the state to have legitimized encroachment on smaller states within the region and the ASEAN network and also creates difficulty in Vietnam’s ability to govern issues like mangrove and coral reef preservation, as well as manage issues like typhoons (Tønnesson 2000). In addition, there is an ontological security angle here. Vietnam sees this encroachment in the Spratly Islands as a threat to Vietnam’s growing power and influence within the region.

Given these disputes and the stakes at play, Vietnam sees the depiction of the nine-dash line on a projected map within the Barbie-verse as a normalization of China’s territorial claims.

Vietnamese public opinion of China

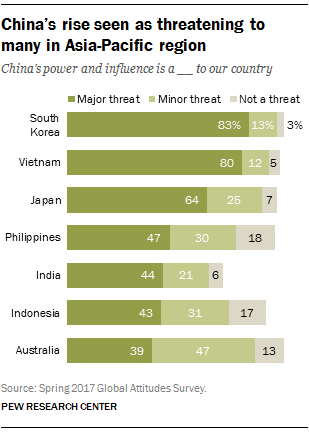

To understand the contemporary opinion of Vietnamese folks towards China, it is helpful to provide a little bit of background of the relationship between the two countries. From 111 BCE (Han Dynasty) to 939 CE, China colonized Vietnam. This relationship through colonization has led to cultural and ideological links (such as a shared Confucian tradition), as well as diplomatic statements jointly issued by Hanoi and Beijing. China was also the first country to recognize the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in 1950. Despite this, land disputes in the 1980s in conjunction with contested land claims in the South China Sea has driven a wedge in the diplomatic relationship between the two countries. In addition, Vietnam’s relationship with the US has been growing over the past several decades, which has also led to some suspicion from China about Vietnam’s allegiances. These factors combined has led to a generally negative Vietnamese public opinion regarding China. As of 2017, 64% of Vietnamese folks surveyed in the Global Attitudes Survey said they found China’s growing economy to be a threat for Vietnam and 90% found China’s military expansion to be a threat to their country. Overall, 80% of Vietnamese respondents found China’s power and influence to be a “major threat” to Vietnam.

China’s role in film production

So, how did we end up with the nine-dash line in the Barbie film to begin with? There are a few theories we can explore. First, it is possible that this was just a design oversight. The average animator or director could very possibly just overlook this detail. However, given the powerhouse production behind this movie (namely, Warner Bros bankroll in the production of it), it seems less likely that this was overlooked.

This brings us to a second possible (and unconfirmed) theory— the inclusion of the nine-dash line was an Easter egg for Chinese film audiences. China represents the world’s largest film market. China, similar to Vietnam, has a censorship board. This board has created a list of off-limits topics or content for films to be screened in China which includes distortions of Chinese history, obscene and vulgar content, as well as “opposing the spirit of the law.” These restrictions lead to so-called “China edits” of films, such as the omission of dialogue implying a gay relationship in another Warner Bros film, “Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore.” Since 2015, Warner Bros has had a partnership with China to produce local-market, Chinese language films.

It is hard to say whether the nine-dash line was meant to intentionally cater to Chinese audiences or not, but this incident does reflect quite a bit about the relationship between film and IR. While many of us have joked about the “Barbieheimer” cross-over double-feature (I’ve booked my tickets already), Barbie’s role in geopolitics should be taken seriously. Barbie really can do it all and Ken is just Ken.